The Era of the Art Fair: CEO Noah Horowitz on Art Basel’s Global Impact

Ahead of the annual shows in Paris and Miami, Horowitz discusses the cultural and financial impact of the globe’s premier contemporary art event

October 1, 2024

Noah Horowitz with Colette by Grace Carney, P•P•O•W gallery, New York City / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

Art Basel CEO Noah Horowitz isn’t used to doing things the old-fashioned way. Before stepping up to lead the largest, most prestigious art fair operator in the world, he was Basel’s director of the Americas, in charge of the company’s most contemporary-leaning show in Miami Beach. Now he turns his attention from one of the youngest major art cities in the world to one of the oldest: Paris.

Launched in 2022, the same year Horowitz became CEO of the company, Art Basel Paris—running this year from October 18 to 20—is the company’s latest endeavor. Renamed from the unwieldy Paris+ par Art Basel, it’s both smaller and more ambitious in scope than its counterparts in Basel, Hong Kong and Miami. With the name change comes a new venue: the Grand Palais, the extraordinary glass-domed exhibition hall built for the 1900 World’s Fair that now functions as an art museum. For its first two years the fair was held in the Grand Palais Éphémère, a temporary venue built in the Champ de Mars to substitute for the original Grand Palais while it underwent renovations in preparation for the Paris Olympics. Both venues hosted events during the Games, with a terrific fencing tournament in the Grand Palais, and now Art Basel will go en garde in the historic venue.

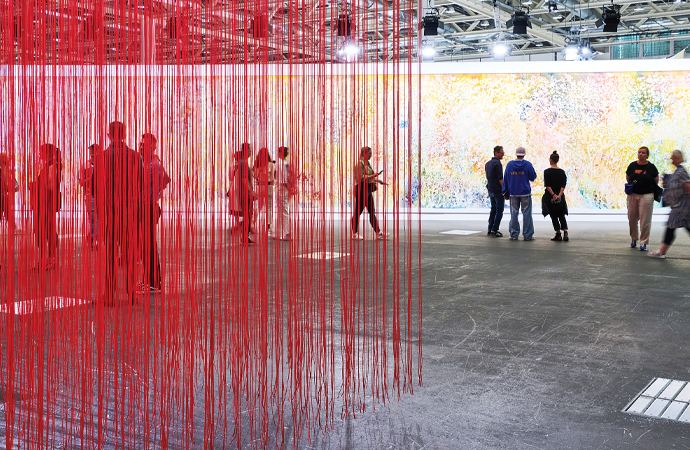

The Extended Line by Chiharu Shiota at Art Basel, Switzerland / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

“It’s a new thing for us,” he says. “Paris is the only Art Basel fair that’s not in a convention center. It’s also the only one of the fairs that’s in a city recognized as a cultural capital with a critical mass and a density of hundreds of galleries at all tiers.”

There are challenges to using a historic venue in the heart of a major city, but to Horowitz, an experienced art-world executive whose résumé includes stints at Sotheby’s and The Armory Show in New York, they’re more like opportunities. While the other Art Basel fairs regularly boast nearly 300 participating galleries—the next one in Miami Beach in December will host 286, for example—they’ve had to keep that number under 200 to make sure they can fit in the Palais. It’s a “jewel box” approach, one prioritizing selectivity over scale. And much like the Olympics, which took place all over the city, Art Basel will use Paris’ abundance of public squares and art institutions to showcase artworks and other projects in iconic locations such as the Place Vendôme, the Petit Palais and the Musée National Eugène-Delacroix.

Art Basel Paris / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

But why Paris? And why now? Beyond its obvious appeal as a cultural destination with arguably the greatest collection of art museums in the world, the French capital has emerged as a confident rival to London as Europe’s art market epicenter. Plenty of art dealers and artists have crossed the channel after the turmoil of the U.K.’s split from the European Union. Blue-chip mega-galleries such as Hauser & Wirth have opened in Paris, and although London’s status as a global banking capital means it’s still ahead in terms of auction sales—for now—that hasn’t stopped Sotheby’s from expanding its presence in France.

Art Basel is at the heart of this renaissance. The fair has brought a more international clientele to the scene than its predecessor in the Grand Palais, the more locally focused FIAC. And much like in its other cities, satellite art fairs such as Design Miami/Paris, Asia Now and Paris Internationale have set up shop, with NADA launching an edition there this year, attracting galleries that couldn’t make the Grand Palais.

“In a post-Brexit world, Paris is attractive now,” Horowitz says. “A lot of artists and galleries have either moved or are now open there. And so for us, we’re extremely excited. It gives Art Basel a further critical touchpoint with our audiences, whether that’s galleries, artists, collectors or institutions. And it creates an even deeper understanding of what our clients are looking for and how we can service them.”

Cotton by Kang Kang Hoon at Art Basel Hong Kong / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

Supercharging a city’s art scene is nothing new for Art Basel. Miami, for instance, was the first beneficiary of the “Basel effect” when the fair opened its first international edition there in 2002. Since its founding in 1970, Art Basel had been one of the major European art fairs and a destination for international collectors, but “the art world was appreciably smaller,” Horowitz says. When Art Basel initially considered expanding, Miami wasn’t even a blip on the radar of the international art market. Yet its status as a crossroads linking North and South America heightened its appeal as a potential destination for artistic commerce.

“If you go back to the mid to late ’90s, when the first conversations about Art Basel expanding started emanating, Miami would not have been the most obvious place in the American market to locate a fair,” Horowitz says. “But there was a really unique bridging between these markets that was highly attractive. There’s always been a very close rapport in South Florida with Latin America broadly. In many ways, Miami is the de facto capital city of South America.”

Un Relato Invisible by Hilda Palafox at Art Basel Miami Beach, Florida / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

In addition, Miami in the ’90s was riding a wave of glamorous renewal driven by the fashion and design industries, a vibrant nightlife scene and a heavy presence of celebrities. Still, it would take more than that to convince Basel, and so some of the city’s most high-profile art collectors, including Craig Robins and Don and Mera Rubell, led a successful charge to bring Art Basel to South Beach.

“When Art Basel landed in Miami in the early 2000s, there was an extraordinary concentration of committed private patrons,” Horowitz explains. “They were integral in bringing and originating the fair, having been familiar with what it was in Basel. But the city as such was not a major cultural destination. There’s long been a community of artists. There have long been cultural institutions in South Florida. But that first decade-plus completely turbocharged the scene. And now, more than 20 years after Art Basel alighted there, Miami sees itself as a city of culture.”

Eternity by Urs Fischer at Art Basel Paris / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

The results speak for themselves. Today Miami is one of the major art world destinations in the Americas and a major economic driver for the entirety of South Florida. The first week in December, when the fair takes place, has ballooned into a massive citywide festival of art, design and parties, with satellite fairs, brand activations, fashion shows and concerts and raves galore. The entire week generates approximately $500 million in economic activity.

Art Basel’s presence has also resulted in a more active gallery scene, especially since the Covid pandemic led to a flood of new and wealthy arrivals to the city. Art museums and other institutions have opened, and existing ones have expanded: The Institute of Contemporary Art Miami opened in 2017 in the Design District, while The Bass museum in Miami Beach got a splashy renovation that same year. Collectors have also driven this growth. The Pérez Art Museum Miami (formerly the Miami Art Museum) moved to a striking Herzog & de Meuron-designed building in 2013, renaming itself after billionaire benefactor Jorge Pérez. Pérez then opened his own museum, El Espacio 23, in 2019, the same year the Rubells moved their collection nearby to a massive, hangarlike space in the industrial neighborhood of Allapattah.

But there has been one unintended consequence of the “Basel effect”: imitators. Art Basel Miami Beach’s success has led to an explosion in art fairs around the globe, with one company in particular beginning to rival Art Basel’s position at the top of the industry. Frieze began in 1991 as an art magazine and started its eponymous fair in London in 2003, a year after Art Basel launched in Miami. London may have been a market focal point with plenty of galleries, but it didn’t have a fair to speak of. Frieze filled the gap, even getting the major auction houses to synchronize the dates of their fall auctions in London with the fair. They expanded to New York, the art market capital of the world, in 2012. Los Angeles and Seoul, two rising art hubs, would follow in 2019 and 2022, respectively. A year after Seoul opened, the company acquired The Armory Show in New York and Expo Chicago.

Yet even Frieze’s rapid rise is just a drop in the bucket compared to the explosive growth of the art fair market. Cities across the globe have turned to the Basel model in the hopes of establishing their own “art weeks” anchored by a major fair: Art SG in Singapore and Art Mumbai in India both debuted in 2023. New York launched its own branded art week in 2022 around Frieze, with four fairs—Independent, TEFAF New York, NADA New York and the Future Fair—all coordinating with auction houses to hold their events simultaneously in early May. Other global cities such as Dubai, Mexico City, São Paulo and Lagos have their own fair weeks, and veterans such as ARCOmadrid in Spain and TEFAF Maastricht in the Netherlands continue to thrive in the new environment. In total, 359 art fairs were held worldwide last year (according to a report by Art Basel and UBS). As Horowitz says, “The last two decades have been broadly characterized as the era of the art fair. And Art Basel Miami Beach led a lot of that transformation.”

Unlike Frieze’s aggressive expansion, Art Basel has expanded more mindfully and cautiously. It only added one additional fair between Miami and Paris: Hong Kong, in 2011. The city was already a major financial center like London and New York and Asia’s de facto art market capital thanks to the presence of major auctioneers, making it less of a risk than Miami. Still, Art Basel’s presence has had a similar stimulating effect: New museums include the M+ for contemporary art and the Hong Kong Palace Museum, a branch of the Forbidden City in Beijing. The number of dealers in Hong Kong has also ballooned, with members of the Hong Kong Art Gallery Association increasing by 27 percent from 2021 to 2023, according to CNBC. Rather than build from scratch as they did in Miami, they’ve leveraged the position of an existing cultural destination and strengthened it, the same tactic they’ve taken in Paris. For Horowitz, building and maintaining the brand means asking how growth can be done mindfully. “It’s less about the prioritization of one fair over another and more about how we as a business need to think much more adeptly in terms of how we differentiate. With four fairs under our purview, each of relatively different scale and orientation, they have to do the right things to service the clients in these markets, as well as the local communities.”

Promise With Him by Ryu In at Art Basel Hong Kong / Photo: Courtesy of Art Basel

All this has helped to maintain the prestige of the Art Basel brand and keep it at the top of the art fair market. A 2024 report by Artsy ranked Basel and Miami second and third, behind only New York, as the “most important art fair cities” to the international art world. The fair’s selectiveness and reputation for showing the pinnacle of art globally is also a key to its continued appeal with buyers. For the Miami Beach fair, gallery applications typically are filed almost a full year in advance of the next edition, according to Bridget Finn, incoming director of Art Basel Miami Beach. Exhibitors are ultimately decided by a special committee of art dealers from around the world, with only the best making the cut.

Finn herself knows the process well, having worked for galleries such as Mitchell-Innes & Nash in New York and her own Reyes | Finn in Detroit. “I have been waitlisted for Art Basel Miami Beach,” she says. “The committee is really tasked with bringing the best galleries to the table and they make very hard decisions for the success of the show. People with great presentations don’t make it into the show, and that is based on space and how many voices we can actually accommodate within the convention center.”

Miami is an excellent case of the need for adaptability, especially as the art market faces broad challenges. After a period of pandemic-induced spending, sales at the three major auction houses, a key bellwether for market health, are down 18 percent from last year, according to data cited by CNBC, with contemporary art sales down 48 percent.

Galleries are also starting to tighten belts. In the Artsy survey cited above, 56 percent of galleries that don’t participate in fairs reported that cost was the biggest reason. Art fairs can be extraordinarily expensive to show at, whether due to the cost of shipping works, personnel, travel, or other factors. It led the fair to introduce new minimum booth sizes, as well as giving dealers the option to share a booth with another gallery. More changes coming this year include a rejiggered floor plan—the Meridians sector, for large-scale works, has been moved to the south side of the convention center, where it will connect Nova and Positions, the two most progressive sections focusing on new work and emerging artists.

Art Basel’s status at the head of the pack also means that it, like the auction houses, is a major market indicator. The success of the fair means success for the wider art market, and vice versa. Balancing these concerns and those of other stakeholders—dealers, buyers, investors, artists—is a massive challenge, but it’s one Horowitz aims to manage with transparency and communication.

“No other art fair is more regularly in touch with its client constituents,” he says. “Day in, day out, our team is interfacing with clients, getting a sense of what direction the wind is blowing and constantly calibrating our offering to what they want to see.”