Making Waves: How Kelly Slater Is Breaking Boundaries

The surfing champion's ventures include a sustainable clothing line and revolutionary wave resorts

by Bill Kearney

April 1, 2024

Competing in Billabong Pipe Masters, 2019 / Photo: Ed Sloane WSL Getty Images

Tube worms and a Florida fishing pier have more to do with the fate of sustainable fashion than you might think. Back in the ’80s, a talented young Cocoa Beach, Florida, surf rat named Kelly Slater was looking for waves big enough to make him a better athlete. That quest led him an hour south to a legendary break at Sebastian Inlet called First Peak.

The pier’s pilings, and the reef that tube worms built at its base, formed an angled wall that reflected waves back out to sea, where they joined forces with following waves, doubling the power. The result was First Peak, the biggest, baddest, funnest wave in Florida. “It was the only wave around that had any energy to it,” says Slater, looking back on his childhood. “It allowed me to learn how to surf waves with a little more power and speed. A really strong contingent of pros surfed there day in and day out, and an intense local crowd.”

Today, First Peak is gone—the pier’s renovation killed the wave reflection. But that experience helped Slater, now 52, evolve into the Tom Brady of surfing. In his pro career he has won the World Surf League Championship 11 times, has 56 Championship Tour victories, and won the Billabong Pro Pipeline at age 49. And he is still competing.

After his win at the Billabong Pro Pipeline, Haleiwa, Hawaii, 2022 / Photo: Koji Hirano/Getty Images

That legendary status gave him enough fame and connections to launch surfwear brand Outerknown in 2015. Traveling to compete in some of the most beautiful places in the world gave him a sense of urgency about sustainability. Today, the company has one of the most ambitious sustainability programs in the industry, one that just might have a tectonic impact on how clothing is manufactured.

As far as bucket lists go, Slater’s is outlandishly complete. He lives in Hawaii. He has traveled the world. The surf accolades are unmatched. His big, startlingly blue eyes, square jaw and broad shoulders earned him modeling gigs with Versace and L’Oréal, as well as the May 1996 cover of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine featuring the line, “Half Fish, Total Dish.” He even had a seven-episode stint on Baywatch opposite Pamela Anderson, whom he dated.

In conversation he’s mellow, but on a wave he takes on the demeanor of a hunting leopard—angular, predatory, fast-twitch, akin to Michael Jordan slicing through the defense. His cutbacks across the face of a wave are both angry and graceful. In one clip, a heavy breaking wave cuts him off. He transforms the head-on collision, somehow, into a lofting pirouette six feet above the tumult. He lands the trick backward, rights his board amid shoulder-high froth and rides out. The television announcers scream in disbelief and Slater smiles as if even he is surprised at what’s possible.

Outerknown, too, almost feels like an experiment in what’s possible, as if Slater and his business partners are asking: Can this actually be done? Can sustainability be profitable? Can the market for sustainable fashion grow enough to bring prices down? Can humans willingly do less harm? Fashion is cutthroat and complex. Add the cost of sustainability and humane conditions for workers and you have a serious challenge.

Even friends were skeptical at first. Slater relays a story that before he could launch Outerknown, he had to leave a 23-year sponsorship relationship with Quiksilver, one of the largest surfwear brands in the world. Over the decades Slater had developed a deep friendship with Quiksilver CEO Pierre Agnes, who has since passed away.

After they severed business ties, they remained close. But when Slater explained the Outerknown concept to him, he was unconvinced. “He told me, ‘This is impossible, what you’re going to try to do,’” says Slater. “He basically said, You’ll be back at Quiksilver soon.” Slater has been calm, even a bit reserved, throughout our conversation, but here he gets animated. “I was like, ‘I don’t think so,’” he says of his reaction to Agnes. “I mean, we’re on a mission here to do this. Even if we do fail, this is a valuable thing for us to try to establish.”

Quiksilver is mass-market fast fashion. What Slater aspires to now is essentially slow fashion. He says he didn’t want to produce cheap logo T’s and printed shirts. “I wanted to make something that felt special, that lasted a long time, that was dear to people.” To that end, every item on the website has a “sustainability” profile explaining the steps the company has taken to make a difference. Garments are made of materials that are for the most part either organic or recycled. The beloved Blanket Shirt, a superthick flannel you’d want to cozy in to after a day on the water, is made of 100-percent organic cotton, and has buttons made of foraged tagua palm nuts as opposed to plastic.

Board shorts are a challenge since they need to be quick-drying and have some stretch, and thus can’t be cotton. Slater developed and surf-tested the Apex Trunks himself. Outerknown found a way to construct them out of 89-percent recycled polyester, five-percent spandex and six-percent recycled spandex. The polyester is made by converting items such as plastic bottles into a new fiber.

Pushing these boundaries is expensive. “We were heavily ridiculed for our price point,” says Slater, “but the raw materials for sustainable fashion cost double, triple. And if you’re going to have it made in a factory that allows people to keep their passports, go home at night and have good working conditions, that costs more, too.”

In the end, the surf lifestyle is about fun, adventure, adrenaline, but Slater wants to sneak in a wee bit of appreciation for the planet that provides those thrills. “We want to do our best to educate without shoving it down people’s throats and being holier than thou,” he says. “You just want to explain and own it. It is a little pricier, but we’re trying to build clothes that last longer and are more special, and at the same time do the right thing by our workers and the environment.”

Surf Ranch

There’s plenty of fun to be had at Slater’s other business venture, Surf Ranch. Located 100 miles from the ocean, in California’s agricultural heartland, it’s a pool with a hydrofoil that runs alongside, pushing water into a wave. Staff can manipulate the foil’s angle and speed to change the wave’s shape and give riders a consistent six- to eight-foot-tall wave. In certain spots the wave arcs over itself into a tube or barrel shape—the holy grail of surfing. People can surf for a lifetime and never catch a barrel. But at Surf Ranch, barrels are automatic.

The concept started gelling around 2005, when Slater got a call from Matt Kechele, his mentor and board shaper when he was a kid. Kechele had seen some wave-pool technology that he thought Slater, with his knowledge, cachet and global connections, could enhance and help get off the ground.

Kelly Slater at his Surf Ranch, Lemoore, California / Photo: Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

Surf Ranch opened in 2015 and now two more properties are in the works: Abu Dhabi will open this spring, and an Austin, Texas, location will break ground this year. Slater says the Austin location is the confluence of all his ideas on community. His friendship with Mike Meldman, who owns global golf-resort-and-residences firm Discovery Land Company, has inspired him. “Mike’s blueprint of what he did for golf was what I was thinking for surfing. You could own a home there, have multiple waves, and be part of this community.”

Austin will get a big barrel wave like California but will also have a wave that’s more “designable.” He’s keeping things close to the vest but says different technology will allow them to essentially emulate the wedge wave at his old haunt First Peak, back in Florida. “You can create different angles with the way you send the energy from the machine into the water,” he says. This will allow waves to meet in novel ways.

Both Surf Ranch and Outerknown are a culmination of his travels, his time bobbing above coral reefs, his late-night conversations with those he has met along the way. Both companies question limits—how sustainable can clothing be? What can an engineered wave be? Slater says he’s inspired by entrepreneurs who have not stayed in their lanes, who have asked, as he has, Can this be done? He says Elon Musk, with both Tesla autos and his audacious space program, comes to mind, as does Yvon Chouinard, who was a leading rock climber before founding outdoor clothing and sustainability juggernaut Patagonia. In 2022, Chouinard and his family transferred ownership of the $3 billion company to a trust designed to use all profits to protect land and fight climate change.

“For me, Outerknown is not about the money,” Slater says. “Of course I want to have a successful brand and employ people for a long time. But if it was about the money I would have stayed at Quiksilver. I wanted to represent people having an idea and doing it if they believe in something.”

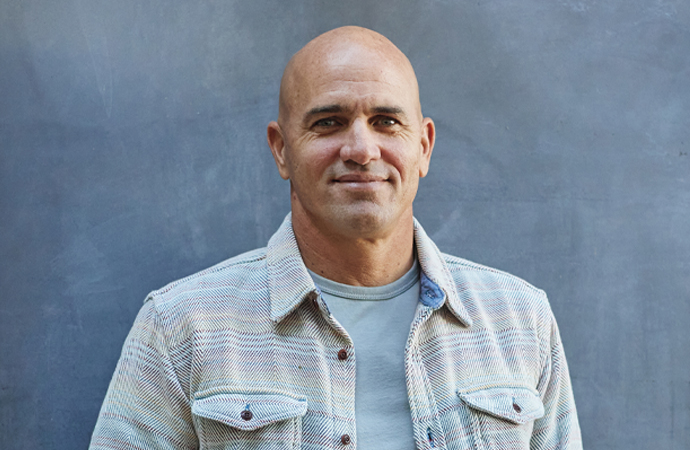

Slater wearing Outerknown’s Blanket Shirt / Photo: Courtesy of Abbra Sharp/Outerknown

The View from the Peak

Now in his 50s, Slater is competing against surfers in their 20s. Talk of retirement is unavoidable. “I haven’t made an official announcement, but I think this’ll be my last year full-time competing,” he says. “But there are three or four events I really love surfing, where I would accept wild cards if I were given them—like Pipeline, Fiji, Tahiti.” He pauses. “Maybe I’ll be able to put a little pressure on those top guys,” he adds, with a layer of mischief in his voice.

Despite all the success, he still pines for Florida. “My real dream is to find an amazing property there, build two or three great waves, get the price to where it’s reasonable for most people and create a community that’s semiprivate. Members have their days and other days are open to the public, so everyone feels that they’re part of the experience. That’s my long-term goal.” He becomes thoughtful for a moment. “I basically moved away so I could chase waves and surf every day. If I could make one in Florida I could just move home and be happy,” he says with a laugh.

He has some guides for his second act, and one in particular. “For almost 30 years I’ve been reading everything I can about Nikola Tesla,” he says. “I became obsessed with what he had done in the world. He said, ‘If you can imagine it, it already exists.’ So basically anything you can think of you can make. I’d like to see more people believe that.”