Architect Bjarke Ingels Is Transforming Landscapes Across the Globe—and Beyond

From New York to Europe to the moon, Ingels is driven to push boundaries

May 1, 2024

Bjarke Ingels with scale models of his buildings in his Brooklyn office / Photo: Ike Edeani

The starriest architects of the 21st century have an immense vision that translates into towering, fully realized projects. Bjarke Ingels is among the brightest. The Danish architect, who moved to New York in 2012, christened his studio BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) in 2006. “It’s been nearly 25 years since I opened my first practice, Plot, in Copenhagen, and most of the people I work with today have been with me a long time,” he tells me over lunch in the glass box boardroom of his Brooklyn office. “We have hired two people a month since we started, and there’s a culture among the team of alignment—we all have a similar way of looking at the world. Every project needs to fulfill someone’s dream, but that doesn’t have to always be my dream, although it’s always my job to make sure we are free to pursue it, no matter who suggested it.”

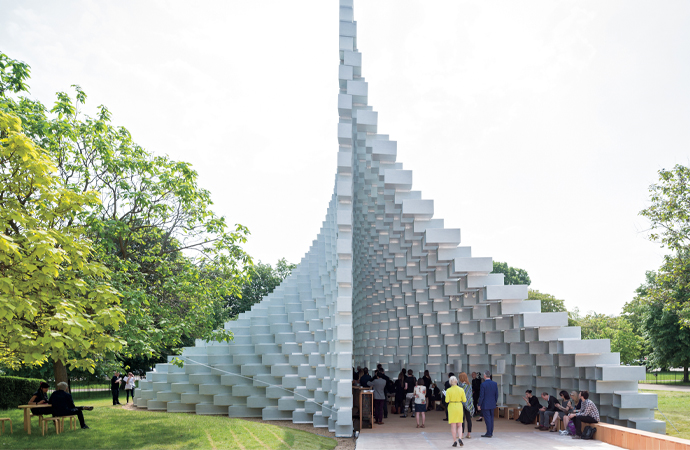

Serpentine Pavilion / Photo: Courtesy of Iwan Baan

Today there are 700 “BIGsters,” as the members of the team are known, working across seven studios in Barcelona, Copenhagen, London, Los Angeles, New York, Oslo and Shenzhen. Ingels has called BIG more of a “movement” than an architectural practice, and it’s one that continues to gain traction. Early projects were largely residential-focused, but on a large scale, including the 11-story Mountain Dwellings in Copenhagen, with a striking sloped roof and gardens and interior surfaces that use blocks of pop color in homage to Verner Panton. Subsequent projects created a tractor beam for media attention: The undulating brick wall of his Serpentine Pavilion in London in 2016 was described as “modular yet sculptural, both transparent and opaque, both solid box and blob.” A year later came the LEGO House, an experience hub for the heritage toy brand in Billund, Denmark. Then there was the Biosphere at the Treehotel in Sweden, and the revelatory CopenHill in Copenhagen—a waste-to-energy plant with a ski slope, climbing wall and running track on top of it.

CopenHill, Copenhagen / Photo: Courtesy of Rasmus Hjortshoj

CopenHill brought the fantasy-fueled nature of Ingels’ work to the fore, embodying the concept of “pragmatic utopia” that the architect sees as core to his practice. So how much heavy lifting is that adjective doing? “Utopia refers to something that is so perfect it can’t exist,” he explains. “It is about the whole world conforming. Pragmatic utopia is about working within the footprint we have available to create the best possible outcome right now.” He points to New York’s Via 57 West, his pyramid-shaped “courtscraper” between Hell’s Kitchen and Lincoln Square, as an example—part skyscraper, part courtyard building, “an attempt to bring the oasis of Central Park down to the scale of a city block.”

Dock A, planned for Zurich Airport / Photo: Courtesy of Imigo

Like all modern architects, Ingels wrestles with the impact of climate change and the critical issue of sustainability, and what they mean for what a building should do as well as look like. One upcoming project is a new airport terminal for Zurich, which will be the largest timber terminal on the planet. “The simplest way to lower the carbon footprint of a building is to replace concrete or steel with timber,” he tells me. “Each time you do it, you reduce the carbon footprint of it 2.2 times.” Along with Via 57, another new BIG landmark for Manhattan is The Spiral, a 66-story tower in Hudson Yards with a ribbon of foliage running up and around its facade, bringing an echo of the green space of the High Line below it into the sky. “It is a mixture of the premodern ziggurat with the modernist glass house,” he says. “It gives each tenant a generous outdoor space.”

Via 57 West, New York City / Photo: Courtesy of Iwan Baan

Ingels looks back to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when he was 15, as what felt like a turning point for a potential utopia, and that image of unity has been constantly inspiring. Today, of course, many see dystopia in abundance, and some of the worst outcomes of science fiction are becoming fact. “It felt like we were all going to unite, slowly and surely,” he says. “But now with world events as they are, it feels like there could be an Archduke Franz Ferdinand moment, triggering a global conflict. But I still don’t think we’re living in dystopian times. We have real issues to deal with, but our biggest challenge is the end of conversation, and the advent of unreconcilable polarization. Cancel culture and the idea that you can’t engage with someone who doesn’t have the same opinion as you is the real dystopian challenge. I consider myself a social liberal, which you might call an oxymoron, but I believe in offering the most freedoms possible to every individual while also showing responsibility towards those in need, the environment, and species that don’t have anyone to advocate for them. We can only find a way forward if both points of view—the libertarians and socialists—are heard. Each project we do, in our oxymoronic way, tries to make free-market mechanisms work in a way to achieve public benefits and environmental goals.”

The shape of our cities has always been a sign of where society is going, and the compact, dense, visually emotive nature of New York—specifically Manhattan—makes it a focus for the global imagination. The ego-driven industrialists of the 1910s and 1920s made their mark on the skyline in a way that hadn’t been seen before. When King Kong scaled the Empire State Building in 1933, the film toyed with the public’s belief that New York was a new and impregnable wonder of the world. The events of 9/11 wiped that away and left a planet traumatized. The fight over the fate of the World Trade Center has been epic, and while One World Trade Center opened in 2014, other elements remain unfinished. Santiago Calatrava’s reimagined St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church only opened in 2022, while Two World Trade Center remains in limbo. A Norman Foster design was axed in favor of an Ingels concept, with large steps of terraces staggered up one side. That too was pulled, with Foster reportedly being called in again to work on a new version of his original design. But Ingels remains immersed in the fabric of New York and will continue to change how it looks. Last year, plans were unveiled for Freedom Plaza, a 4.1 million-square-foot development next to the United Nations building, which will bring “affordable housing” to this stretch of the East River, along with a museum and hotel.

With so much time being spent on megaprojects in the city, does Ingels now feel like a “New York architect”? “Well,” he says, “I am in the city most of the time, and my son goes to school here. We have substantial projects ongoing on both coasts, as well as the Tennessee Performing Arts Center in Nashville, but I still feel as much at home in Copenhagen as I do in New York. I think that’s what defines what we do—at the core of everything is an attempt to create ideas that reconcile and resolve seemingly contradictory elements into a single project. So, the ‘courtscraper,’ for instance, is the unlikely encounter of the European courtyard with the verticality and density of an American skyscraper.”

Mountain Dwellings, Copenhagen, Denmark / Photo: Courtesy of Iwan Baan

Like the ski slope on top of the recycling plant in Copenhagen, the result of looking to reconcile and resolve often leads to a hybrid building. His Kistefos museum in Norway is a museum, bridge and piece of sculpture in its own right. Plans for the CityWave building in Milan incorporate what will be the largest solar farm in any European city. And the aforementioned timber building for the Zurich Airport is a concept that embraces numerous green issues, with a poetic sense of place and identity. Airports tend to be liminal spaces, but as anyone who has traveled through an insufficiently air-conditioned hub in tropical Southeast Asia or tried (and failed) to get a glass of wine in Marrakesh Menara will testify, they aren’t neutral spaces that exist in a vacuum. For Dock A at ZRH, Ingels wants to create something as immediately enjoyable as it is sustainable: “You always want to land in an airport that feels representative of the city and country you are arriving in,” he says. “If your flight arrives at Terminal E, the non-Schengen satellite building in Zurich, you’re in a beautiful, brutalist, concrete space. Then you take the underground tunnel through excavated rocks, and you hear cowbells.” Ingels is talking about the unique audio-visual element of the airport shuttle at ZRH, where an actor voicing the part of Heidi welcomes you to the country and invites you to look out of the windows at a cleverly animated LED display of villages and mountains. “I think that’s really interesting,” he says. “So we thought about the new building at the end of that as a kind of timber brutalism—with a Swiss honesty to the design, a straightforwardness and simplicity, but with a sensuality, because if you use that amount of timber, it will smell like the biggest Swiss chalet ever built.”

Kistefos museum, Jevnaker, Norway / Photo: Courtesy of Kyrre Sundal

Design is all about questions and problems, answers and solutions. Is shade essential? How about reinforcements from seismic forces? “Depending on where you are in the world, and what resources you have available, the answer to the question you pose with architecture will look very different,” says Ingels. “Mainland Europe is cold in the winter, reasonably dry, with no aggressive environment from salt water, so sustainably grown timber is a great material to use, and there is an abundance of it within 90 minutes by road from the Zurich Airport.” When BIG entered the competition for the new dock at ZRH, they were up against their key rivals at Foster + Partners. The plans for an all-timber structure were romantic and appealing, but cost was an issue. “Then Covid happened, and the international supply chain collapsed,” says Ingels. “Russia invaded Ukraine and energy prices rocketed. Suddenly the use of timber was no longer a big risk or cost, comparatively.”

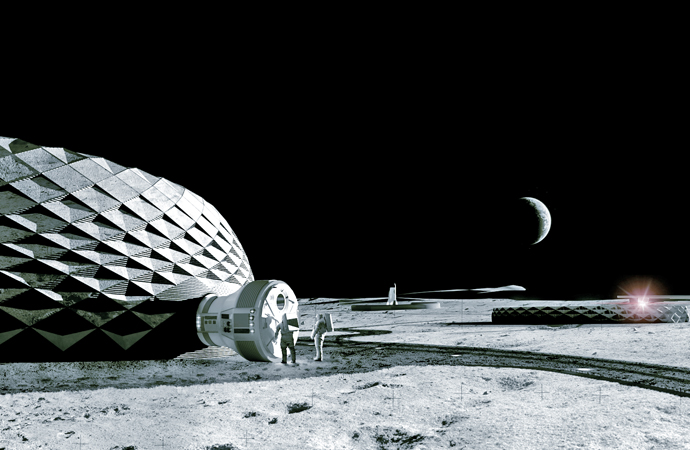

Anyone facing a layover in Zurich won’t get to experience the BIG-designed Dock A anytime soon. All such projects involve logistical spaghetti, and construction doesn’t start until 2030, by which point Ingels believes some of his work will be part of a permanent habitat established, or at least under construction, on the moon. At the India Today Conclave in New Delhi in March, Ingels spoke about his work with NASA on Project Olympus, which aims to create 3D-printed structures using materials found on the moon’s surface. This goes in tandem with his work that would literally go even farther—Mars Science City is a project to make habitation of the Red Planet feasible by 2117. A prototype campus, with pressurized biodomes and robots, is planned for outside Dubai.

Project Olympus, planned for the moon / Photo: Courtesy of BIG

These are all immense projects, coming from someone with limitless vision. Are they all plausible? Perhaps not. But Ingels remains driven to push boundaries. “We arrive at breakthroughs by piling on, rather than taking away,” he says. “We are currently working on a series of 3D-printed pavilions for the El Cosmico campsite in Marfa, which is a linear project, working with local sand and gravel in a desert vernacular. But then there’s The Vltava Philharmonic Hall in Prague, which sits on a highway, next to a train bridge, over a metro line, and has multiple orchestras that use it and so many acoustic requirements.”

Ingels has designed 121 buildings that have been completed to date. When each was finished, a scale model 1:1000 was printed and placed with its siblings on a table in the reception area of BIG in Brooklyn. The smallest is the modular Klein A45 cabin, “which looks like a speck of dust,” and the biggest is The Spiral, “which looks like it could eat all of the others without gaining a square foot.” But, as he says, “A project is a project, a building is a building.” And they are all BIG, in their own way.